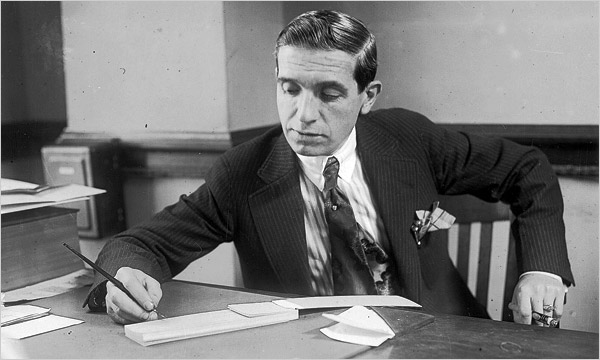

charles ponzi

Charles Ponzi, (born Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi) (March 3, 1882 – January 18, 1949), was an Italian swindler and con artist in the U.S. and Canada. His aliases include Charles Ponci, Carlo, and Charles P. Bianchi. Born and raised in Italy, he became known in the early 1920s as a swindler in North America for his money-making scheme. He promised clients a 50% profit within 45 days, or 100% profit within 90 days, by buying discounted postal reply coupons in other countries and redeeming them at face value in the United States as a form of arbitrage. In reality, Ponzi was paying earlier investors using the investments of later investors. While this swindle predated Ponzi by several years, it became so identified with him that it now bears his name. His scheme ran for over a year before it collapsed, costing his “investors” $20 million.

Ponzi may have been inspired by the scheme of William F. Miller, a Brooklyn bookkeeper who in 1899 used the same scheme to take in $1 million. In addition, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo”, Charles Deville Wells, had operated a very similar scheme in France in 1910–11, when—under the alias ″Lucien Rivier″—he had set up a phony bank, to the detriment of his 6,000 victims.

Early life

Charles Ponzi was born in Lugo, Italy, in 1882. He told The New York Times that he had come from a family in Parma, Italy. His ancestors had been well to do, and his mother continued to use the title “Dona”, but the family had subsequently fallen upon bad days and had little money. He took a job as a postal worker early on, but soon was accepted into the University of Rome La Sapienza. His richer friends considered the university a “four-year vacation,” and he was inclined to follow them around to bars, cafés, and the opera. This resulted in Ponzi spending all his money, and four years later he was broke and without a degree. During this time, a number of Italian boys were migrating to the United States and returning to Italy as rich people. Ponzi’s family encouraged him to do the same thereby returning his family to its lost glory.

Arrival in the United States

On November 15, 1903, he arrived in Boston aboard the S.S. Vancouver. By his own account, Ponzi had $2.50 in his pocket, having gambled away the rest of his life savings during the voyage. “I landed in this country with $2.50 in cash and $1 million in hopes, and those hopes never left me,” he later told The New York Times. He quickly learned English and spent the next few years doing odd jobs along the East Coast, eventually taking a job as a dishwasher in a restaurant, where he slept on the floor. He managed to work his way up to the position of waiter, but was fired for shortchanging the customers and theft.

Move to Montreal and Banco Zarossi

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

In 1907, after some years of failing to do well in the USA, Ponzi moved to Montreal and became an assistant teller in the newly opened Banco Zarossi, a bank started by Luigi “Louis” Zarossi to service the influx of Italian immigrants arriving in the city. By this time, Ponzi had a charming cheerful personality and spoke French, English and Italian, which Zuckoff says helped him get the job at Banco Zarossi. It was here that Ponzi first saw the scheme of “Robbing Peter to pay Paul” (which subsequently would be called Ponzi scheme). Zarossi paid 6% interest on bank deposits – double the going rate at the time – and was growing rapidly as a result. Ponzi eventually rose to bank manager. However, he found out that the bank was in serious financial trouble because of bad real estate loans, and that Zarossi was funding the interest payments not through profit on investments, but by using money deposited in newly opened accounts. The bank eventually failed and Zarossi fled to Mexico with a large portion of the bank’s money.

Ponzi stayed in Montreal and, for some time, lived at Zarossi’s house helping the man’s abandoned family, while planning to return to the United States and start over. As Ponzi was penniless, this proved to be very difficult. Eventually he walked into the offices of a former Zarossi customer Canadian Warehousing and, finding no one there, wrote himself a check for $423.58 in a checkbook he found, forging the signature of a director of the company, Damien Fournier.

Confronted by police who had taken note of his large expenditures just after the forged check was cashed, Ponzi held out his hands wrist up and said “I’m guilty.” He ended up spending three years at St. Vincent-de-Paul Federal Penitentiary, a bleak facility located on the outskirts of Montreal. Rather than inform his mother of this development, he posted her a letter stating that he had found a job as a “special assistant” to a prison warden.

After his release in 1911 he decided to return to the United States, but got involved in a scheme to smuggle Italian illegal immigrants across the border. He was caught and spent two years in Atlanta Prison. Here he became a translator for the warden, who was intercepting letters from mobster Ignazio “the Wolf” Lupo. Ponzi ended up befriending Lupo. It was another prisoner who became a true role model to Ponzi: Charles W. Morse. Morse, a wealthy Wall Street businessman and speculator, fooled doctors during medical exams by eating soap shavings to give the appearance of ill-health. Morse was soon released from prison. Ponzi completed his prison term following Morse’s release, having an additional month added to his term due to his inability to pay a $50 fine.

Work in a mining camp and in Boston

After Ponzi’s release from prison, he made his way back to Boston. While working at a mining camp as a nurse, he came up with the idea of going to a mining camp, starting a utility there that would supply water and power, and selling its stock. During this time, a fellow nurse called Pearl Gosid had suffered severe burns in an accident. Despite not knowing her, Ponzi volunteered to two major operations to donate 220 square inches of his skin from his back and legs to Pearl. This resulted in pleurisy and similar complications and his losing his job.

Thereafter he continued to travel around looking for work, and in Boston, he met Rose Maria Gnecco, a stenographer, to whom he proposed marriage. Though Ponzi did not tell Gnecco about his years in jail, his mother sent Gnecco a letter telling her of Ponzi’s past. Rose came from a family of Italian-American immigrants who had a small fruit stall in Downtown Boston. Nonetheless, she married him in 1918. For the next few months, he worked at a number of businesses, including his father-in-law’s grocery, and the import-export company JR Poole before hitting upon an idea to sell advertising in a large business listing to be sent to various businesses. Ponzi was unable to sell this idea to businesses, and his company failed soon after. He took over his wife’s now failing family fruit company for a while, but to no avail and it too failed.

Origin of the term “Ponzi scheme” and IRC scheme

An idea to trade IRCs

During this time, in the summer of 1919, he decided to stop working for other people and set up his own small office at 27 School Street, in Boston, coming up with ideas and writing to people he knew in Europe trying to sell them as opportunities. A few weeks later, Ponzi received a letter from a company in Spain asking about the advertising catalog. Inside the envelope was an international reply coupon (IRC), something which he had never seen before. He asked about the IRC and found a weakness in the system which would, in theory, allow him to make money.

The purpose of the postal reply coupon was to allow someone in one country to send it to a correspondent in another country, who could use it to pay the postage of a reply. IRCs were priced at the cost of postage in the country of purchase, but could be exchanged for stamps to cover the cost of postage in the country where redeemed; if these values were different, there was a potential profit. Inflation after World War I had greatly decreased the cost of postage in Italy expressed in U.S. dollars, so that an IRC could be bought cheaply in Italy and exchanged for U.S. stamps of higher value, which could then be sold. Ponzi claimed that the net profit on these transactions, after expenses and exchange rates, was in excess of 400%. This was a form of arbitrage, or profiting by buying an asset at a lower price in one market and immediately selling it in a market where the price is higher, which is completely legal.

Seeing an opportunity, Ponzi quit his translator’s job to set his IRC scheme in motion, but needed a large capital outlay to buy these IRCs at cheaper European currencies. He first tried to borrow money from banks including the Hanover Trust Company to buy these IRCs, but they were not convinced and its manager, Shimelensky, turned him down.

Undaunted, Ponzi set up a stock company to raise this money from the public. He also went to several of his friends in Boston and promised that he would double their investment in 90 days. He later shortened this to 45 days at 50% interest, thus doubling one’s money in three months. This was in an environment when banks were paying 5% annual interest. The great returns available from postal reply coupons, he explained to them, made such incredible profits easy. Some people invested and were paid off as promised, receiving $750 interest on initial investments of $1,250.

Securities Exchange Company

Soon afterward, in January 1920, Ponzi started his own company, the “Securities Exchange Company,” to promote the scheme. In the first month, 18 people invested in his company with a total of $1800. He paid them promptly next month, with the money obtained from the newer set of investors. He set up a larger office, this time in the Niles Building on School Street. Word spread, and investments came in at an ever-increasing rate. Ponzi hired agents and paid them generous commissions for every dollar they brought in. By February 1920, Ponzi’s total take was US $5,000 (approximately US $54,000 in 2010 dollars). By March 1920, he had taken in $25,000 ($324,000 in 2010 terms). A frenzy was building, and Ponzi began to hire agents to take in money from all over New England and New Jersey. At that time, investors were being paid impressive rates, encouraging others to invest. By May 1920, he had made $420,000 ($4.53 million in 2010 terms). By June 1920, people had invested $2.5 million in Ponzi’s scheme. By July, he was raking in a million dollars per week and rising. By the end of July, he was approaching a million dollars per day.

He began depositing the money in the Hanover Trust Bank of Boston (a small bank on Hanover Street in the mostly Italian North End), in the hope that once his account was large enough he could impose his will on the bank or even be made its president; he bought a controlling interest in the bank through himself and several friends after depositing $3 million. By July 1920, he had made millions. People were mortgaging their homes and investing their life savings. Most did not take their profits, but reinvested. Ponzi’s company meanwhile had set up branches from Maine to New Jersey.

Ponzi was bringing in cash at a fantastic rate of nearly a million dollars per day, but the simplest financial analysis would have shown that the operation was running at a large loss. As long as money kept flowing in, existing investors could be paid with the new money. This was the only way Ponzi had to pay off those investors, as he made no effort to generate legitimate profits.

Ponzi’s initial investors consisted of worker immigrants just like him. Gradually news travelled upwards, and many well to do Boston Brahmins also invested in his scheme. In its heyday, nearly 75% of Boston’s police force had invested in Ponzi’s scheme. Ponzi’s investors included his chauffeur John Collins, Ponzi’s own brother in law, and young newspaper boys investing a few dollars, as well as wealthy people including a banker from Lawrence who invested $10,000.

The unfeasibility of Ponzi’s scheme

Though Ponzi was still paying back investors (mostly from money from subsequent investors), he had not yet figured out a way to actually change the IRCs to cash. He also subsequently realized that changing the coupons to money was a logistical impossibility. For example: for the initial 18 investors of January 1920, for their $1700 investment, it would have taken 53,000 postal coupons to actually realize the arbitrage profits. For the subsequent 15,000 investors that Ponzi had, he would have had to fill Titanic sized ships with Postal coupons just to ship them to the United States from Europe. However, Ponzi found that all the interest payments returned to him, as investors kept re-investing

Ponzi’s subsequent lifestyle

Ponzi lived luxuriously: he bought a mansion in Lexington, Massachusetts, and he maintained accounts in several banks across New England besides Hanover Trust. He bought a locomobile, the finest car of that time. He had initially bought two first class tickets to Italy for a delayed honeymoon with Rose, but instead decided to change them to bring his mother from Italy to America in a first-class stateroom on an ocean liner. She lived with Ponzi and Rose for some time in Lexington, but died soon after. On July 31, 1920, Ponzi told Father Pasquale Di Milla, the director of the Italian Children’s Home in Jamaica Plain, that he would donate $100,000 in honor of his mother. Ponzi also bought a macaroni company and part of a wine company in an attempt to gain profits that could be used to repay the investors of his IRC scheme.

Suspicion

Ponzi’s rapid rise naturally drew suspicion. When a Boston financial writer suggested there was no way Ponzi could legally deliver such high returns in a short period of time, Ponzi sued for libel and won $500,000 in damages. As libel law at the time placed the burden of proof on the writer and the paper, this effectively neutralized any serious probes into his dealings for some time.

Nonetheless, there were still signs of his eventual ruin. Joseph Daniels, a Boston furniture dealer who had given Ponzi furniture which he could not afford to pay for, sued Ponzi to cash in on the gold rush. The lawsuit was unsuccessful, but it did start people asking how Ponzi could have gone from being penniless to being a millionaire in so short a time. There was a run on the Securities Exchange Company, as some investors decided to pull out. Ponzi paid them and the run stopped.

On July 24, 1920, the Boston Post printed a favorable article on Ponzi and his scheme that brought in investors faster than ever. At that time, Ponzi was making $250,000 a day. Ponzi’s good fortune was increased by the fact that just below this favorable article, which seemed to imply that Ponzi was indeed returning 50% return on investment after only 45 days, was a bank advertisement that stated that the bank was paying 5% returns annually. The next business day after this article was published, Ponzi arrived at his office to find thousands of Bostonians waiting to give him their money.

Despite this reprieve, Post acting publisher Richard Grozier (also the son of the editor and owner of the Post) and city editor Eddie Dunn were suspicious and assigned investigative reporters to check Ponzi out. He was also under investigation by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and, on the day the Post printed its article, Ponzi met with state officials. He managed to divert the officials from checking his books by offering to stop taking money during the investigation, a fortunate choice, as proper records were not being kept. Ponzi’s offer temporarily calmed the suspicions of the state officials.

Collapse of the scheme

By this time, Ponzi was seeking another deal to get him out of trouble, but time was running out. On July 26, the Post started a series of articles that asked hard questions about the operation of Ponzi’s money machine. The Post contacted Clarence Barron, the financial journalist who headed Dow Jones & Company, to examine Ponzi’s scheme. Barron observed that though Ponzi was offering fantastic returns on investments, Ponzi himself was not investing with his own company.

Barron then noted that to cover the investments made with the Securities Exchange Company, 160 million postal reply coupons would have to be in circulation. However, only about 27,000 actually were. The United States Post Office stated that postal reply coupons were not being bought in quantity at home or abroad. The gross profit margin in percent on buying and selling each IRC was colossal, but the overhead required to handle the purchase and redemption of these items, which were of extremely low cost and were sold individually, would have exceeded the gross profit. Barron noted that if Ponzi really was doing what he claimed to do, he would effectively be profiting at the expense of a government—either the governments where he bought the coupons or the United States government. For this reason, Barron argued that even if Ponzi’s operation was legitimate, it was immoral to take advantage of a government in this manner.

The stories caused a panic run on the Securities Exchange Company. Ponzi paid out $2 million in three days to a wild crowd outside his office. He canvassed the crowd, passed out coffee and donuts, and cheerfully told them they had nothing to worry about. Many changed their minds and left their money with him. However, this attracted the attention of Daniel Gallagher, the United States Attorney for the District of Massachusetts. Gallagher commissioned Edwin Pride to audit the Securities Exchange Company’s books—an effort made difficult by the fact his bookkeeping system consisted merely of index cards with investors’ names.

In the meantime, Ponzi had hired a publicity agent, William McMasters. However, McMasters quickly became suspicious of Ponzi’s endless talk of postal reply coupons, as well as the ongoing investigation against him. He later described Ponzi as a “financial idiot” who did not seem to know how to add.

The denouement for Ponzi began in late July, when McMasters found several highly incriminating documents that indicated Ponzi was merely “robbing Peter to pay Paul.” He went to his former employer with this information. Grozier offered him $5,000 for his story. On August 2, 1920, McMasters wrote an article for the Post declaring Ponzi hopelessly insolvent. The article claimed that while Ponzi claimed $7 million in liquid funds, he was actually at least $2 million in debt. With interest factored in, McMasters wrote, Ponzi was as much as $4.5 million in the red. The story touched off a massive run, and Ponzi paid off in one day. He then sped up plans to build a massive conglomerate that would engage in banking and import/export operations.

Trouble now came from an unexpected quarter—Massachusetts Bank Commissioner Joseph Allen. An initial investigation into Ponzi’s banking practices found nothing illegal, but Allen was afraid that if major withdrawals exhausted Ponzi’s reserves, it would bring Boston’s banking system to its knees. Allen’s suspicions were further aroused when he found out a large number of Ponzi-controlled accounts had received more than $250,000 in loans from Hanover Trust. This led Allen to speculate that Ponzi wasn’t nearly as well-financed as he claimed, since he was getting large loans from the bank he effectively controlled. He ordered two bank examiners to keep an eye on Ponzi’s accounts.

On August 9, the examiners reported that enough investors had cashed their checks on Ponzi’s main account there that it was almost certainly overdrawn. Allen then ordered Hanover Trust not to pay out any more checks from Ponzi’s main account. He also orchestrated an involuntary bankruptcy filing by several small Ponzi investors. The move forced Massachusetts Attorney General J. Weston Allen to release a statement that there was little to support Ponzi’s claims of large-scale dealings in postal coupons. State officials then invited Ponzi note holders to come to the Massachusetts State House to furnish their names and addresses for the purpose of the investigation. On the same day, Ponzi received a preview of Pride’s audit, which revealed Ponzi was at least $7 million in debt.

On August 11, it all came crashing down for Ponzi. First, the Post came out with a front-page story about his activities in Montreal 13 years earlier—including his forgery conviction and his role at Zarossi’s scandal-ridden bank. That afternoon, Bank Commissioner Allen seized Hanover Trust due to numerous irregularities. The commissioner thus inadvertently foiled Ponzi’s plan to “borrow” funds from the bank vaults as a last resort in the event all other efforts to obtain funds failed.

By the morning of August 12, Ponzi knew he was at the end of his tether. He held a certificate of deposit at Hanover Trust that was worth $1.5 million, but that total had been reduced to $1 million after bank officials tapped into it to cover the overdraft. Even if he had been able to convert it into cash, he would have had only $4 million in assets. Amid reports that he was about to be arrested any day, Ponzi surrendered to federal authorities that morning and accepted Pride’s figures. He was charged with mail fraud for sending letters to his marks telling them their notes had matured. He was originally released on $25,000 bail and was immediately re-arrested on state charges of larceny, for which he posted an additional $10,000 bond. After the Post released the results of the audit, the bail bondsman feared Ponzi might flee the country and withdrew the bail for the federal charges. Attorney General Allen declared that if Ponzi managed to regain his freedom, the state would seek additional charges and seek a bail high enough to ensure Ponzi would stay in custody.

Magnitude of losses

The news brought down five other banks in addition to Hanover Trust. His investors were practically wiped out, receiving less than 30 cents to the dollar. His investors lost about $20 million in 1920 dollars (225 million in 2011 dollars): Charles Ponzi completely annihilated their finances. As a comparison, Bernard Madoff’s similar scheme that collapsed in 2008 cost his investors about $18 billion, 53 times the losses of Ponzi’s scheme.

Prison and later life

In two federal indictments, Ponzi was charged with 86 counts of mail fraud, and faced a lifetime in prison. At the urging of his wife, Ponzi pleaded guilty on November 1, 1920, to a single count before Judge Clarence Hale, who declared before sentencing, “Here was a man with all the duties of seeking large money. He concocted a scheme which, on his counsel’s admission, did defraud men and women. It will not do to have the world understand that such a scheme as that can be carried out … without receiving substantial punishment.” He was sentenced to five years in federal prison.

Massachusetts

He was released after three and a half years and was almost immediately indicted on 22 Massachusetts state charges of larceny, which came as a surprise to Ponzi; he thought he had a deal calling for the state to drop any charges against him if he pleaded guilty to the federal charges. He sued, claiming that he would be facing double jeopardy if Massachusetts essentially retried him for the same offenses spelled out in the federal indictment. The case, Ponzi v. Fessenden, made it all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. On March 27, 1922, the Supreme Court ruled that federal plea bargains have no standing regarding state charges. It also ruled that Ponzi was not facing double jeopardy because Massachusetts was charging him with larceny while the federal government charged him with mail fraud, even though the charges implicated the same criminal operation.

In October 1922, he was tried on the first ten larceny counts. Since he was insolvent, Ponzi served as his own attorney and, being as persuasive as he had been with his duped investors, the jury found him not guilty on all charges. He was tried a second time on five of the remaining charges, and the jury deadlocked. Ponzi was found guilty at a third trial, and was sentenced to an additional seven to nine years in prison as “a common and notorious thief.” Remarkably, during his various prison terms, he continued to receive Christmas cards from some of his more gullible investors, as well as requests from others to invest their money—from his prison cell.

After word got out that Ponzi had never obtained American citizenship (despite having lived in the United States for most of the time since 1903), federal officials initiated efforts to have him deported as an undesirable alien in 1922.

Florida

Ponzi was released on bail as he appealed the state conviction, and fled to the Springfield neighborhood of Jacksonville, Florida, and launched the Charpon Land Syndicate (“Charpon” is an amalgam of his name), offering investors in September 1925 tiny tracts of land, some under water, and promising 200% returns in 60 days. In reality, it was a scam that sold swampland in Columbia County. Ponzi was indicted by a Duval County grand jury in February 1926 and charged with violating Florida trust and securities laws. A jury found him guilty on the securities charges, and the judge sentenced him to a year in the Florida State Prison. Ponzi appealed his conviction and was freed after posting a $1,500 bond.

Ponzi traveled to Tampa, where he shaved his head, grew a mustache, and tried to flee the country as a crewman on a merchant ship bound for Italy. The ship, however, made one last American port of call; he was caught in New Orleans and sent back to Massachusetts to serve out his prison term. Ponzi served seven more years in prison.

In the meantime, government investigators tried to trace Ponzi’s convoluted accounts to figure out how much money he had taken and where it had gone. They never managed to untangle it and could conclude only that millions had gone through his hands.

Italy

Ponzi was released in 1934. With the release came an immediate order to have him deported to Italy. He asked for a full pardon from Governor Joseph B. Ely. However, on July 13, Ely turned the appeal down. His charismatic confidence had faded, and when he left the prison gates, he was met by an angry crowd. He told reporters before he left, “I went looking for trouble, and I found it.” On October 7, Ponzi was officially deported.

Rose stayed behind, and divorced him in 1937. She had not wanted to leave Boston, and Ponzi was in no position to support her in any event.

In Italy, Ponzi jumped from scheme to scheme, but little came of them. He eventually got a job in Brazil as an agent for Ala Littoria, the Italian state airline. During World War II, however, the airline’s operation in the country was shut down after the British intelligence services intervened and Brazil sided with the Allies. During that time, Ponzi also wrote his autobiography.

Death

Ponzi spent the last years of his life in poverty, working occasionally as a translator. His health suffered. A heart attack in 1941 left him considerably weakened. His eyesight began failing, and by 1948, he was almost completely blind. A brain hemorrhage paralyzed his right leg and arm. He died in a charity hospital in Rio de Janeiro, the Hospital São Francisco de Assis of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro on January 15, 1949.

Supported by his last and only friend who spoke English and had notions of Italian, barber Francisco Nonato Nunes, Ponzi granted one last interview to an American reporter, telling him, “Even if they never got anything for it, it was cheap at that price. Without malice aforethought, I had given them the best show that was ever staged in their territory since the landing of the Pilgrims! It was easily worth fifteen million bucks to watch me put the thing over.”